EARLY

INCEPTIONS

HISTORY

Benevolent societies of early American history acted as a medium of communication and "sense of racial solidarity between cities". In a time during or following slavery, these organization were vital in assisting recently emancipated slaves and fore melding free Blacks into a community. Scholar Robert L. Harris states, "they played a key role in the creolization of Africans in American society [and] functioned as the wellspring for Afro-American institutional life" (Harris). According to The First Annual Report of the American Moral Reform Society, "benevolent societies were the most widespread type of association among free Afro-Americans in the five states surveyed (Ma

voluntary associations were not mirror-images or exaggerated forms of similar white organizations", but instead grew and developed alongside white organizations. (Harris). Because of the contrasting life experiences and needs, black benevolent societies served different functions than their white counterparts. The major features of black benevolent societies were sickness and disability benefits, pensions for deceased members' families, burial insurance, funeral direction, cemetery plots, credit unions, charity, education, moral guidance, and discussion forums. The free black community formed following "the American Revolution when the free black population, clustered in urban areas, fused into an identifiable organism as a result of its efforts in black benevolent societies to meet the challenges of freedom" (Harris). Importantly, "the early black benevolent societies as

The first black benevolent society was the African Union Society. This organization was established in 1780 in Newport, Rhode Island in order "to promote the local black population's welfare by assisting its members in time of need" (Harris). In many ways, "local black voluntary associations were the cement that joined together different elements of the free black population in major urban centers, especially in the North" (Harris) . Because of the notably different racial climate, southern black societies were less likely to establish benevolent societies for black communities. However, where they were established successfully, these organizations "became a mechanism for southern free Blacks to gain some semblance of community, although more limited in scope than for their northern counterparts and in many instances rigidly adhering to the region's social strictures" (Harris). Harris says, "often, they had to meet secretly to avoid suspicion, the arrest of their members, and the destruction of their organizations. Most southern states, particularly after slave uprisings, passed and enforced legislation against the congregation of more than a few Blacks, slave or free, without white supervision".

RACE RELATIONS & RESPECTABILITY POLITICS

As aforementioned, black benevolent societies existed in very white spaces with pressure from their counterparts to adhere to social constructs, so naturally, Politics of Respectability played a large role in the function of these organizations. In fact, "the regulation of their members' moral conduct was an important aspect of most black benevolent societies" (Harris). Records show that the Free African Society of Philadelphia expelled a member for abandoning his wife and child to live with another woman (Harris). Philadelphia's own Brotherly Union Society also provided for the trial of any member "guilty of fraudulent, base, or immoral conduct" (Harris). These voluntary associations were also selective in their membership. In states like Louisiana and South Carolina, in an effort to preserve black Creole's or Mulattoes status, "the criteria for membership in some groups included wealth, education, and a speaking knowledge of French" (Jacobs). Boston's African Society specified that "applicants had to be sponsored by three members in good standing, [and] any member who brought a disability on himself because of intemperance was not eligible for benefits' (Harris).

GENDER

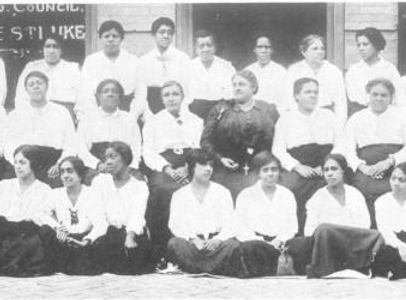

While black benevolent societies helped to propel the community forward, intersections of gender still plagued these organizations as many women were not allowed membership to these soieties. As a general rule, "females belonged to those voluntary associations which stressed education. Whether it was because of financial requirements or the emphasis on black males as heads of households, black women were not ordinarily members of the benevolent societies with disability benefits, burial expenses, and credit as major functions" (Harris). Nonetheless, women took the initiative to begin their own organizations. Notably, "one of the earliest groups for which records exist was the Female Benevolent Society of St. Thomas, a mutual aid society established in Philadelphian 1793" (Scott). In 1809, when the African Benevolent Society of Newport refused to let women vote or hold office, women set up their own organization to care for each other and for the poor in their community (Scott). Importantly, these female auxillaries, like their male counterparts, were also particularly conscious of public perception of themselves. By 1830 there were at least 27 female mutual aid societies in Philadelphia alone, one of which was comprised of nearly two hundred working-class women who pooled their tiny savings to help each other during sickness, unemployment, or family troubles (Scott). A more "elite" group met weekly for "mental improvement in moral and literary pursuits." (Scott). These women made important contributions to the literary world, as they began writing articles for the Liberator and raised money for Frederick Douglass's abolitionist paper, North Star.

PROMINENT SOCIETIES

Listed below is a list of prominent benevolent societies both in the north and south.

-

New York African Society for Mutual Relief (1808)

-

the African Clarkson Society

-

Wilberforce Benevolent Society

-

the African Wool man Benevolent Society of Brooklyn

-

Absolute Beneficial Society of Washington, D.C. (1818)

-

the Burying Ground Society (1815), Virginia

-

Beneficial Society of Richmond (1815), Virginia

-

Brown Fellowship Society (1790),Charleston, South Carolina

-

Christian Benevolent Society (1839),Charleston, South Carolina

-

Humane Brotherhood (1843),Charleston, South Carolina

-

Unity and Friendship Society (1844), Charleston, South Carolina